Domain name registrars like Tucows operate in a complex environment that both grants and inhibits our authority. Working through the various players and layers will take us on a winding path.

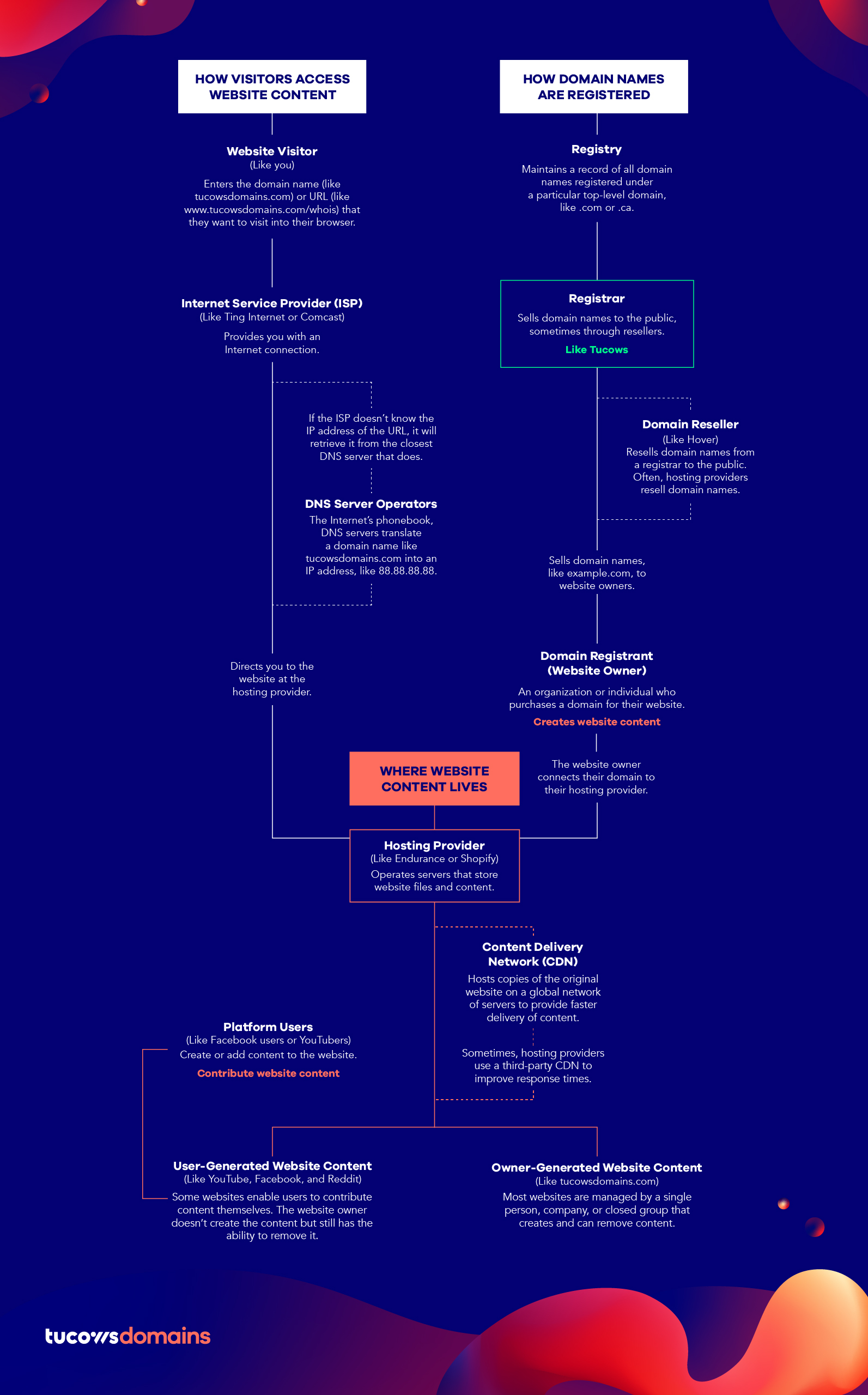

To begin, here’s a high-level overview of the DNS ecosystem’s basic structure:

When you want to register a new domain name (e.g., example.com), you choose a registrar such as Tucows—or perhaps a reseller that buys on your behalf from a registrar; you probably won’t know or care whether it’s a reseller or a registrar. The registrar buys the domain on your behalf from a registry, which holds the records for all domains in that TLD (top-level domain, such as .com or .org).

When you want to build a website that people can reach by going to your domain name, you’ll probably choose a web hosting service to provide site-building tools and maybe some server space. When you set up your website, you’ll tell your registrar to associate the domain name with the “nameservers” your webhost provides; nameservers connect the domain name to the web hosting service.

Once all that is set up, when a user types your domain name into a browserA computer application that displays and navigates between web pages. (such as Chrome, Safari, or Firefox), the browser will look up your domain’s nameservers and will be sent to the IP address of your site; an IP address is a series of numbers (and sometimes letters), such as “192.0.43.7” or “2620:0:2d0:200::7”, that identifies your hosted data.

The actual process is much more complex than that, because everything that happens on the Internet is more complicated than it seems. But that’s a rough overview.

The flow of authority is even more complex.

What a registrar can do

As a registrar, we have only one tool, and it’s not a precise one. All we can do is make a domain name unresolvable. This means that any content on a website associated with that domain will remain online, still accessible on the Internet by typing in its IP address, but not by typing in the domain name.

This is why we always encourage people with complaints about website content to contact the web hosting provider: they are the entities that can remove content. (At Tucows, our reseller-partners are often also the web hosting provider.)

How authority flows

What follows is a simplified explanation (we swear!) of where a registrar’s authority comes from:

The DNS (Domain Name System) is the global system that translates the user-friendly domain names we’re all familiar with into the numeric addresses of Internet sites, much like an old-timey phone book did. That’s why you can just type “icann.org” into your browser to visit that site rather than having to enter its IPv4 address: 192.0.43.7 (or its IPv6 address: 2620:0:2d0:200::7).

ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) is the governing body that manages the DNS. This means that any registry or registrar that wants to provide domain names has to work with ICANN.

A registry manages the database that keeps all of the DNS information necessary for a top-level domain (TLD) to run. A TLD is the last part of a domain: in example.com, it’s “.com”; in “example.co.uk”, it’s “.uk”. A TLD may be generic (e.g., .com) or belong to a country (e.g., .uk, which belongs to the United Kingdom).

A registrar registers and manages domain names, usually on behalf of a registrant, the person or organization who wants a domain name. To do so, the registrar has to agree both to the ICANN Registrar Accreditation Agreement (RAA) and each registry’s contract (a Registry-Registrar Agreement, or RRA). By signing these contracts, the registrar agrees to collect contact information from domain owners, display some of that information in a public Whois record, provide transfer authorization codes upon valid request, respond to reports of certain types of abuse, and more.

ICANN-accredited registrars and registries must also follow Consensus Policies created by the ICANN Community, a multi-stakeholder group of people interested in the Internet and the DNS, and approved by its Board of Directors. The ICANN Community develops policy in working groups made up of members who represent the various stakeholders within the ICANN Community, including registrars and registries. The ICANN Community also includes non-commercial and not-for-profit users, business and intellectual property groups, Internet service providers, governmental advisors, security researchers, and people who represent Internet users at large. The Consensus Policies that emerge from these working groups, however, must remain strictly within the boundaries of ICANN’s remit, which is the administration of the Domain Name System.

If the registrar refuses to comply with its obligations under the RAA—for example, it doesn’t update contact information upon notification by the domain owner (registrant)—the ICANN Contractual Compliance team can send a ticket to the registrar instructing them to address the issue. ICANN Contractual Compliance’s mission, derived from ICANN’s operating bylaws, is to “preserve the security, stability and resiliency of the Domain Name System and to promote consumer trust.” If ICANN Contractual Compliance finds that a registrar has violated the terms of the RAA, it can remove that registrar’s ability to act as a registrar. This rarely happens. (We at Tucows wish it would happen more often. And faster.)

Finally, in 2019, a group of registrars and registries—independent of ICANN structures—drafted the DNS Abuse Framework. Tucows is pleased to be one of its framers and among the first signers. The Framework not only clearly defines DNS Abuse, it also discusses some content-related situations where a registrar is encouraged to take action (such as CSAM, human trafficking, and incitements to violence).

Most often, when someone has a complaint about a domain name, the complaint is actually about the content of a website hosted on that domain name. You are always welcome to report to us concerns about a website using a domain name registered with us. That page also includes a discussion of what types of concerns we can help you with and what we do when we receive your complaint.

Our Report Abuse page discusses at length how Tucows handles reports of DNS Abuse and other bad things online.

A method to the Internet’s madness

The Internet is a crazy place. We love it.

Of course, we don’t love all of the Internet. Literally no one does. Here at Tucows we especially hate sites that make the world worse for the most vulnerable.

So, what do we do when we get complaints about sites that are hateful and disgusting but not illegal?

We govern our behavior by two principles.

- Play by the rules.

There are three main sources of rules for registrars:

- A registrar has to obey the laws of the jurisdictions that it operates in. For Tucows, those jurisdictions are Canada, Denmark, Germany, and the United States because we have a local presence in each of those four countries.

- Registrars must agree to follow ICANN’s contractual obligations and consensus-based policies; adherence is monitored and enforced by ICANN’s Contractual Compliance department.

- Tucows has voluntarily committed to adhere to the DNS Abuse Framework, which it helped draft. It specifies categories of abuse that we act on. We support and operate under that Framework.

Usually, following these three sets of rules is straightforward. Sometimes, though, doing what’s right and obeying the rules seem to conflict.

That’s why our second rule is:

- The Golden Principle of Self-Doubt: We can never be totally sure what the right thing to do is.

For Tucows, that means we: a) Act carefully, trying to be aware of our own biases and privilege; b) We provide avenues of appeal; and c) When appropriate, we consult with experts.

There is one more consequence of the Golden Principle of Self-Doubt, and it’s especially important: Be transparent.